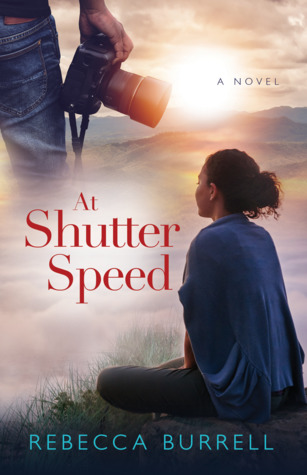

At Shutter Speed

Rebecca Burrell

Publication date: May 1st 2018

Genres: Adult, Contemporary

In the click of a shutter, #Resistance becomes more than just a hashtag.

Pass the bar exam. Convince someone—anyone—in the Egyptian government to admit they’ve imprisoned your husband. Don’t lose your mind. For fledgling human rights attorney Leah Cahill, the past six months have been a trial by fire, ever since Matty, a respected but troubled war photojournalist, disappeared during a crackdown in Cairo.

Leah, the daughter of a civil rights icon, grew up wanting to change the world; Matty was the one who showed her she could. Though frustrated by the US government’s new fondness for dictators, she persists, until a leaked email reveals a crumbling democracy far closer to home.

Risking her own freedom, she gains proof Matty’s being detained at a U.S. ‘black site’, stemming from his work covering the refugee crisis in Syria. Armed with his photo archives, Leah plunges into their past together, a love story spanning three continents. She uncovers secrets involving Matty’s missionary childhood, her own refugee caseload, and the only story the deeply principled reporter ever agreed to bury. It’s what got him captured—and what might still get him killed. With Leah’s last chance to save him slipping away, Matty’s biggest secret may be one he’s willing to die to protect.

—

EXCERPT:

As far as the world is concerned, Matty is one of hundreds missing in the crackdown. Amnesty classifies him as a prisoner of conscience, but between shooting, imprisoning, and brutalizing every journalist and dissident they can get their hands on, Egypt denies they have him. Reporters Without Borders says ‘Missing, whereabouts and welfare unknown’. The network that sent him to Cairo washed their hands of the whole thing as soon as the first ransom demand came in. ‘Due to Mr. Cahill’s status as a freelance journalist, we regret that we are unable to provide further assistance. Mr. Cahill was advised of the need to provide his own kidnap insurance’. Most of our friends think he’s dead, which isn’t a possibility I’m willing to consider. At least not out loud. But in the lonely, small hours of the night, sometimes I wake up talking to his ghost.

To hear people talk, I’ve gone off the deep end. ‘He’s obviously dead, she’s in denial. She’s better off without him anyway.’ ‘His own fault, going those places.’ Social media? Forget it. Turns out, posting an appeal for a captured journalist is a surprisingly effective way to generate rape threats.

The fact is, the ‘kidnap insurance’ Matty was supposed to buy cost more than the assignment paid. He covered the Syrian Civil War in Russian surplus body armor he bought on Craigslist. We both knew the risks. But not getting Matty back means accepting a world where journalism is expendable. Even the truth itself. If fighting that makes me crazy, then so be it.

I found this tiny apartment after he disappeared, a one-bedroom off Columbus Circle. A bay window overlooks the street, floor to ceiling bookcases in the hall, filled with framed photos and books, plus dozens of sandpipers Matty had carved out of driftwood while we were shacked up with my parents. He’d spend hours watching them dart along the shore, lost in his thoughts.

Oops, like me. Late for work.

I’m wearing his favorite T-shirt, which doesn’t smell like him anymore, but I pretend it does. I slip it off, then throw on a navy skirt suit—the universal female junior associate attire. It’s my suit of armor, defense against the whispers that I only have a job because of my dad, but it can’t stop me from feeling like a fraud on the inside. Silly old Leah can’t even get the Egyptian Government to answer her inquiries anymore.

After grabbing a pair of heels, I run out the door. Though I know Matty would yell at me for doing it, I leave it unlocked. I always do. Just in case.

The days after he vanished are a blurred nightmare, stumbling through fields of bodies in the makeshift morgues, until my visa got revoked and the State Department threw me on a plane home. The first thing I did was call the firm to let them know I couldn’t take the job. Not with Matty’s trail growing colder by the second. One of the founders, Julie Coventry, who’d clerked for my dad back in the day, picked my ass off the floor and drove me to the bar herself. ‘Pull it together. You’ll need your license. You’ll need our resources. You’ll need advice. This is not the time to go it alone.’

Junior associates at God & Coventry—nicknamed for either the other founder’s legal reputation or the fact he’s approximately six thousand years old—carry between fifteen and twenty cases. Including Matty, I have thirty-two. It’s partly because immigration attorneys who speak passable Arabic are few and far between, partly because the administration hasn’t met an immigrant it doesn’t want to deport, and partly because I begged for the extra work. If I stop moving, I’ll drown.

What it means on this particular day is that I have to be at the courthouse by eight a.m. to ambush a judge who makes a game of hiding from lawyers who need his signature, because if I’m not, one of my thirty-two clients will be deported to his home country and killed. I have to be at the firm by nine a.m. to meet with Julie for my thrice-delayed performance review, which is about to get delayed a fourth time because I have to go and prostrate myself in front of Senator Nance to get Immigration to stop sitting on a different asylum petition that’s about to expire. Which would undoubtedly go better if I hadn’t lost it with him last week over a ‘sanctuary city’ defunding provision he caved on, because apparently, refugees are only worth saving if they’re victims or saints instead of ordinary, flawed people like the rest of us. Basically? It’s going to be a fun morning.

Brushing raindrops from my hair, I sprint up the courthouse steps, after spotting Judge Lawrence Q. Underwood skulking behind the Civil War monument by the south entrance. It’s judiciary-only, which means I have to use the western entrance, take my chances with the pervy security guard because his line is invariably shorter, and then catch Underwood before he reaches his office, because the lawyer-hating architect who designed the courthouse thought it would be great to have separate corridors for judges, juries, defendants and attorneys, so none of us ever have to talk to each other. Except when we do. Which Underwood finds hilarious.

Panting, I catch the old coot as he ducks into the sixth-floor men’s room. With peaked grey eyebrows, bowed legs and an overstuffed belly, he’s a chimera of a horned owl and a basset hound. He waves his copy of the Post. “Nature calls, Counselor. You’ll have to wait.”

I debate following him, but rumor has it the last attorney who did found his client on a plane to Uganda an hour later. “Your honor, it won’t take a minute,” I say, pushing the door a crack. “I just need a signature.”

All I get is a fart and a whistle. To the tune of the United Airlines theme song.

“I’ll be outside, your honor.”

Author Bio:

In her own fictional world, Rebecca Burrell is a secret Vatican spy, a flight nurse swooping over the frozen battlefields of Korea, or a journalist en-route to cover the latest world crisis. In real life, she's a scientist in the medical field. She lives in Massachusetts with her family, two seriously weird cats, and a dog who's convinced they're taunting him.

Guest Post with Rebecca Burrell

The Space Between: Plotting and Pantsing

Religion versus Science. Cat Person versus Dog Person. Red Sox versus Yankees. In the storied canon of intractable debates, few things generate as much passion amongst authors as the choice between plotter and pantster. Sides are chosen, the trenches are dug. But is there a middle ground?

A pantster might find the idea of having to write a synopsis or outline like a stranglehold on their creativity. For a plotter, the idea of working without a net may feel disorganized or even paralyzing. For me personally, there are aspects of both approaches that I struggle with. When I do outline, it tends to turn into this enormous, detailed document describing key scenes or even exchanges of dialogue between characters. But then, as the saying goes, no battle plan survives contact with the enemy. As soon as I start writing, the characters take the wheel and nothing goes as I expect. My ten page outline derails somewhere around the third paragraph, or my word count is clearly going to be three times too long, and oops, it’s back to the drawing board. Or the 80k words I was allotted start looking like they’re going to be 120k. On the other hand, if at that point I ditch it and just let fly, I usually end up stuck and flailing, not knowing where the story goes next.

For me, the solution turns out to be blending the two approaches. (Plotsing?) Rather than a detailed outline, I flesh out a set of three broad-stroke turning points, along with an inciting incident. Usually I sketch out the ending as well, but sometimes I can’t see it when I’m starting out. Each turning point represents an escalation of the tension in the story, and each must make it more difficult (preferably impossible) for the character to turn back. Each one takes the form ‘What is my character’s problem, how does she try to solve it, and what are the consequences of that attempt?’ I find that doing it this way allows me to retain the magic of discovering how the character reacts to a particular situation while still ensuring that the story is driving somewhere at a pace that’s appropriate for the story. If you’ve written yourself into the corner and can’t get out, or if your outline has become a tombstone, take a step towards the middle and try it out!

No comments:

Post a Comment